I’m legally blind. That’s a well-known fact about me at this point. But just in case, being legally blind means that I still have a (in my case, considerable) amount of eyesight but that it’s nowhere near enough to go through life without struggling. Reading is something I’ve struggled with almost my whole life - unless the font is large and bold enough, and the right colors are used (typically a dark color scheme), I…just can’t read. You can imagine that makes computers difficult to use. But thanks to assistive technology like screen readers, text-to-speech and screen magnifiers, it’s nowhere near as hard as it could be.

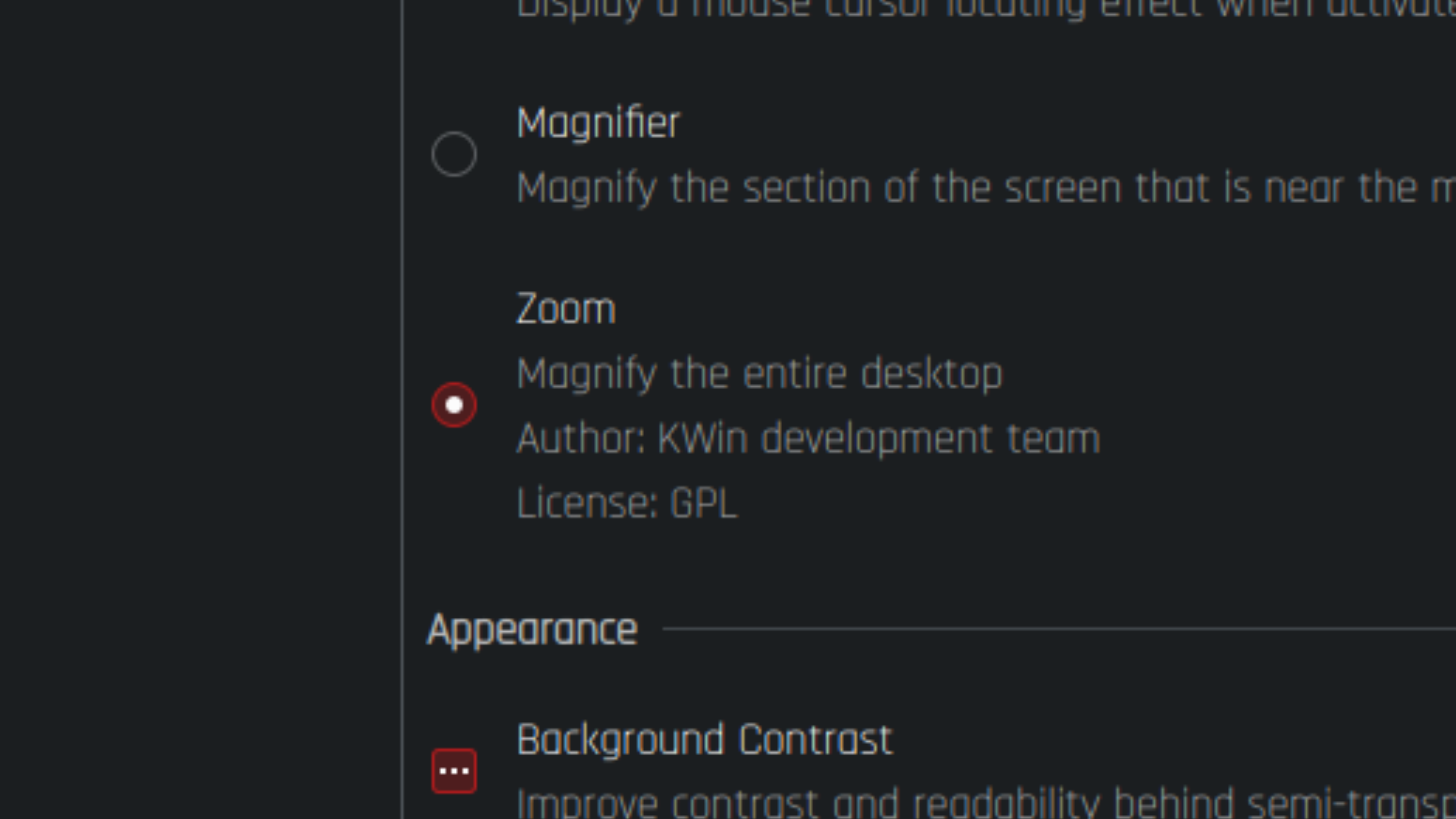

The topic of this post is screen magnifiers. I’m going to talk you through how I found and fixed a bug in KDE Plasma’s screen magnifier, a fix that is now merged into KDE Plasma 6. I also want to use this opportunity to explain why I think KDE’s magnifier is one of the best, and what other desktop environments and Wayland compositors can learn from it.

Background: How we got here

I grew up on Microsoft Windows. It’s what we used in school, it’s what all my computers at home always ran, it’s what I’m used to. But it’s not perfect, every major OS release changes or breaks at least one thing in a way that makes computers harder for me to enjoy using. However one of the best versions of Windows I’ve ever used, and I’d imagine this holds true for many of you as well, was Windows 7.

Windows 7 was the first version of Windows to introduce the modern Windows Magnifier, adding proper support for full-screen desktop zoom via the Desktop Window Manager added in Windows Vista. Its core behaviour remains unchanged, even in Windows 11, save for a few default settings being changed. So you can try it right now if you’re running Windows. Here are the controls.

- To exit Magnifier, press

WINDOWS KEY+Esc. You may want to immediately if you feel lost. - To open Magnifier or to zoom in, press

WINDOWS+=. - To zoom out, press

WINDOWS+-. - To toggle color inversion, press

CTRL+ALT+I.

The only downside in Windows 7, is that fullscreen zoom requires Aero. Using the Basic, Classic or High Contrast themes will disable full-screen zoom and the Magnifier will fall back to a docking panel like the one in Vista and earlier versions of Windows.

Microsoft addressed this in Windows 8 by adding the Aero Lite theme to the system. This is a visual style that still uses the DWM, but is much lighter on system resources than traditional Aero or the new Metro visual style. It was used on Windows RT as the default theme, but was also used by the High Contrast themes. This meant you could now have High Contrast and fullscreen zoom in Windows 8. This carries over even into Windows 11.

But we all know what Windows also started to do as of Windows 8. It started to become a genuinely annoying, privacy-invasive, telemetry-riddled operating system full of forced advertisements and first-party bloatware you may never use but also aren’t allowed to uninstall. While I liked Windows 8, and could tolerate Windows 10, this lead many people to jump ship over to Linux. I started my journey of using Linux on-and-off all the way back in 2011, when my sight was considerably better.

However I could never use Linux full-time, even with better sight. I still needed Windows for school, and gaming was also nowhere near as possible back then as it is today. So I kept going back to Windows, and wouldn’t come back to Linux for sometimes years at a time.

Fast-forward to the 2020s, I’m now a grown-up, no longer in school, Proton exists, and now all of these reasons I need Windows are addressed by the Linux community. Well, all but one - my severe blindness, and much worse vision than what I had as a kid. The introduction of Wayland also complicated the Linux desktop, making it that little bit harder to use.

I’ve been jumping between Linux and Windows every few months for the past 3 years, and the issue sending me back to Windows every time has always been my blindness. No desktop environment or compositor properly implements a screen magnifier for the Linux desktop. Many desktops have one, but in a lot of cases it’s nowhere near as functional as I need. Some of them actually cause visual corruption of the screen if you have multiple monitors like me… So that’s not great.

While none of them are perfect, the best magnifier by far is the KWin Zoom effect built-in to KDE Plasma.

It’s so good, that many distros including Arch ship the effect enabled by default. It even has the same hotkeys as Windows, so you already know how to use it. (Color inversion is a different effect in KDE, and that doesn’t count.)

So what’s the issue?

I mentioned that no Linux screen magnifier is perfect, and I wasn’t kidding. KDE’s isn’t perfect either, and I’d know - because I’m writing this article and I’m the one who fixed one of the major issues with it.

Before Plasma 6 was released, I put out this video on YouTube showing a bug in KDE 5.27’s magnifier.

The video demonstrates a bug that I posted to KDE Bugzilla several months earlier, which can be found at https://bugs.kde.org/show_bug.cgi?id=467182.

The gist of it is: If you have more than one monitor, arranged in such a way that your screens don’t form a perfect rectangle, you will be unable to reach certain areas on your desktop when using the Push mouse tracking mode.

Hold on there, what’s mouse tracking?

When using a screen magnifier, you need to be able to move it around your desktop. How this is done depends on the magnifier, but generally involves your mouse. Mouse tracking is how the magnifier moves the zoom area based on where your cursor is and how it moves. In KDE, it’s configurable in the zoom effect settings. There are four modes.

- Proportional: the default and the worst. This mode moves the zoom area exactly where the mouse moves. It’s incredibly disorienting.

- Center: Similar to Proprtional, but it will prefer to keep the mouse in the center of your workspace. I haven’t tested this on multiple screens, but on a single screen, it will make the mouse cursor stay in the center of your screen unless it physically can’t (because you’re too close to an edge)

- Push: The one you should be using. This one makes it so the zoom area moves only if you push the mouse against an edge of the desktop. This makes it natural to position the zoom area over some text to read, then move the mouse out of the way.

- Disabled: Not sure why you would ever want or use this, but this makes it so the magnifier never tracks the mouse so you cannot pan it with the mouse.

The bug I found was in the third setting, Push.

What’s wrong with the code?

Let’s look at the code from the zoom effect from sometime long before I fixed the issue.

void ZoomEffect::paintScreen(const RenderTarget &renderTarget, const RenderViewport &viewport, int mask, const QRegion ®ion, Output *screen)

{

OffscreenData *offscreenData = ensureOffscreenData(renderTarget, viewport, screen);

if (!offscreenData) {

return;

}

// Render the scene in an offscreen texture and then upscale it.

RenderTarget offscreenRenderTarget(offscreenData->framebuffer.get(), renderTarget.colorDescription());

RenderViewport offscreenViewport(viewport.renderRect(), viewport.scale(), offscreenRenderTarget);

GLFramebuffer::pushFramebuffer(offscreenData->framebuffer.get());

effects->paintScreen(offscreenRenderTarget, offscreenViewport, mask, region, screen);

GLFramebuffer::popFramebuffer();

const QSize screenSize = effects->virtualScreenSize();

const auto scale = viewport.scale();

// mouse-tracking allows navigation of the zoom-area using the mouse.

qreal xTranslation = 0;

qreal yTranslation = 0;

switch (mouseTracking) {

case MouseTrackingProportional:

xTranslation = -int(cursorPoint.x() * (zoom - 1.0));

yTranslation = -int(cursorPoint.y() * (zoom - 1.0));

prevPoint = cursorPoint;

break;

case MouseTrackingCentred:

prevPoint = cursorPoint;

// fall through

case MouseTrackingDisabled:

xTranslation = std::min(0, std::max(int(screenSize.width() - screenSize.width() * zoom), int(screenSize.width() / 2 - prevPoint.x() * zoom)));

yTranslation = std::min(0, std::max(int(screenSize.height() - screenSize.height() * zoom), int(screenSize.height() / 2 - prevPoint.y() * zoom)));

break;

case MouseTrackingPush: {

// touching an edge of the screen moves the zoom-area in that direction.

int x = cursorPoint.x() * zoom - prevPoint.x() * (zoom - 1.0);

int y = cursorPoint.y() * zoom - prevPoint.y() * (zoom - 1.0);

int threshold = 4;

xMove = yMove = 0;

if (x < threshold) {

xMove = (x - threshold) / zoom;

} else if (x + threshold > screenSize.width()) {

xMove = (x + threshold - screenSize.width()) / zoom;

}

if (y < threshold) {

yMove = (y - threshold) / zoom;

} else if (y + threshold > screenSize.height()) {

yMove = (y + threshold - screenSize.height()) / zoom;

}

if (xMove) {

prevPoint.setX(std::max(0, std::min(screenSize.width(), prevPoint.x() + xMove)));

}

if (yMove) {

prevPoint.setY(std::max(0, std::min(screenSize.height(), prevPoint.y() + yMove)));

}

xTranslation = -int(prevPoint.x() * (zoom - 1.0));

yTranslation = -int(prevPoint.y() * (zoom - 1.0));

break;

}

}

// use the focusPoint if focus tracking is enabled

if (isFocusTrackingEnabled() || isTextCaretTrackingEnabled()) {

bool acceptFocus = true;

if (mouseTracking != MouseTrackingDisabled && focusDelay > 0) {

// Wait some time for the mouse before doing the switch. This serves as threshold

// to prevent the focus from jumping around to much while working with the mouse.

const int msecs = lastMouseEvent.msecsTo(lastFocusEvent);

acceptFocus = msecs > focusDelay;

}

if (acceptFocus) {

xTranslation = -int(focusPoint.x() * (zoom - 1.0));

yTranslation = -int(focusPoint.y() * (zoom - 1.0));

prevPoint = focusPoint;

}

}

// Render transformed offscreen texture.

glClearColor(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0);

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

auto shader = ShaderManager::instance()->pushShader(ShaderTrait::MapTexture);

for (auto &[screen, offscreen] : m_offscreenData) {

QMatrix4x4 matrix;

matrix.translate(xTranslation * scale, yTranslation * scale);

matrix.scale(zoom, zoom);

matrix.translate(offscreen.viewport.x() * scale, offscreen.viewport.y() * scale);

shader->setUniform(GLShader::Mat4Uniform::ModelViewProjectionMatrix, viewport.projectionMatrix() * matrix);

offscreen.texture->render(offscreen.viewport.size() * scale);

}

ShaderManager::instance()->popShader();

if (mousePointer != MousePointerHide) {

// Draw the mouse-texture at the position matching to zoomed-in image of the desktop. Hiding the

// previous mouse-cursor and drawing our own fake mouse-cursor is needed to be able to scale the

// mouse-cursor up and to re-position those mouse-cursor to match to the chosen zoom-level.

GLTexture *cursorTexture = ensureCursorTexture();

if (cursorTexture) {

const auto cursor = effects->cursorImage();

QSizeF cursorSize = QSizeF(cursor.image().size()) / cursor.image().devicePixelRatio();

if (mousePointer == MousePointerScale) {

cursorSize *= zoom;

}

const QPointF p = (effects->cursorPos() - cursor.hotSpot()) * zoom + QPoint(xTranslation, yTranslation);

glEnable(GL_BLEND);

glBlendFunc(GL_SRC_ALPHA, GL_ONE_MINUS_SRC_ALPHA);

auto s = ShaderManager::instance()->pushShader(ShaderTrait::MapTexture | ShaderTrait::TransformColorspace);

s->setColorspaceUniformsFromSRGB(renderTarget.colorDescription());

QMatrix4x4 mvp = viewport.projectionMatrix();

mvp.translate(p.x() * scale, p.y() * scale);

s->setUniform(GLShader::Mat4Uniform::ModelViewProjectionMatrix, mvp);

cursorTexture->render(cursorSize * scale);

ShaderManager::instance()->popShader();

glDisable(GL_BLEND);

}

}

}

This is the screen painting code for the zoom effect. A lot of it is very unimportant for this article, so don’t worry if you’re overwhelmed. But this is the first thing I looked for when I tried to fix the issue, so I want to take you guys down the journey I went through.

We need to look for the part of the code that deals with mouse tracking. Luckily, a little bit of CTRL + F in an IDE will get you where you need to go. If we look for case MouseTrackingPush, we’ll find this code.

case MouseTrackingPush: {

// touching an edge of the screen moves the zoom-area in that direction.

int x = cursorPoint.x() * zoom - prevPoint.x() * (zoom - 1.0);

int y = cursorPoint.y() * zoom - prevPoint.y() * (zoom - 1.0);

int threshold = 4;

xMove = yMove = 0;

if (x < threshold) {

xMove = (x - threshold) / zoom;

} else if (x + threshold > screenSize.width()) {

xMove = (x + threshold - screenSize.width()) / zoom;

}

if (y < threshold) {

yMove = (y - threshold) / zoom;

} else if (y + threshold > screenSize.height()) {

yMove = (y + threshold - screenSize.height()) / zoom;

}

if (xMove) {

prevPoint.setX(std::max(0, std::min(screenSize.width(), prevPoint.x() + xMove)));

}

if (yMove) {

prevPoint.setY(std::max(0, std::min(screenSize.height(), prevPoint.y() + yMove)));

}

xTranslation = -int(prevPoint.x() * (zoom - 1.0));

yTranslation = -int(prevPoint.y() * (zoom - 1.0));

break;

}

I’m sure you can agree, this is a much more manageable piece of code. So let’s try and figure out what it’s doing.

Code analysis

Let’s look at what KDE 5.27’s zoom push tracking code does.6

- First we get the position of the mouse within the zoom area inside

xandy. - We then define a constant threshold value of

4. - Two variables are zeroed out,

xMoveandyMove. These define how far and in what direction we’ll move the zoom area this frame. - The next 4

ifstatements are an inner-bounds check againstx,yand thescreenSize. We make sure thatxandydon’t leavescreenSize’s defined rectangular area, applyingthresholdunits worth of an inner margin. - If

xMoveisn’t zero, then we need to move horizontally byxMove. So we apply the movement distance to the zoom area, making sure the zoom area doesn’t go outside of thescreenSizerectangle. - We do the same for

yMove, this time moving vertically if we need to. - We calculate

xTranslationandyTranslationbased on where the zoom area is now, and this is how we know at what offset to render the screen later on.

So now that we know what the code’s doing and how it works, where’s the bug?

Well…there’s a reason I posted the full code of the method this push tracking code is in. The bug is really hard to notice unless you know what the fix was.

Let’s look at where screenSize comes from.

const QSize screenSize = effects->virtualScreenSize();

As you can see, it’s just a QSize variable (representing a width and a height) that stores the result of calling effects->virtualScreenSize().

We can use our IDE to inspect the virtualScreenSize() method and find out what header it’s defined in. We can find it in effecthandler.h, and it’s documented.

/**

* The bounding size of all screens combined. Overlapping areas

* are not counted multiple times.

*

* @see virtualScreenGeometry()

* @see virtualScreenSizeChanged()

* @since 5.0

*/

QSize virtualScreenSize() const;

The bounding size of all screens combined. Overlapping areas are not counted multiple times.

So, screenSize will be the size of all screens combined, excluding overlapping areas. So, if you have one 10x10 screen and another 20x10 screen next to it, you’ll get 30x10. If you have a 20x20 and a 20x40 screen side-by-side, aligned at the top edges, then you’ll get 40x40.

It also means that, if you have a 100x100 screen at 0x25, and another one at 100x0, you will get 200x125.

Furthermore, when the zooom effect uses screenSize in the push tracking code, it is treated as an implied rectangle. This rectangle will be (0, 0) with a size of, well, screenSize. This is what causes the bug.

How the bug works

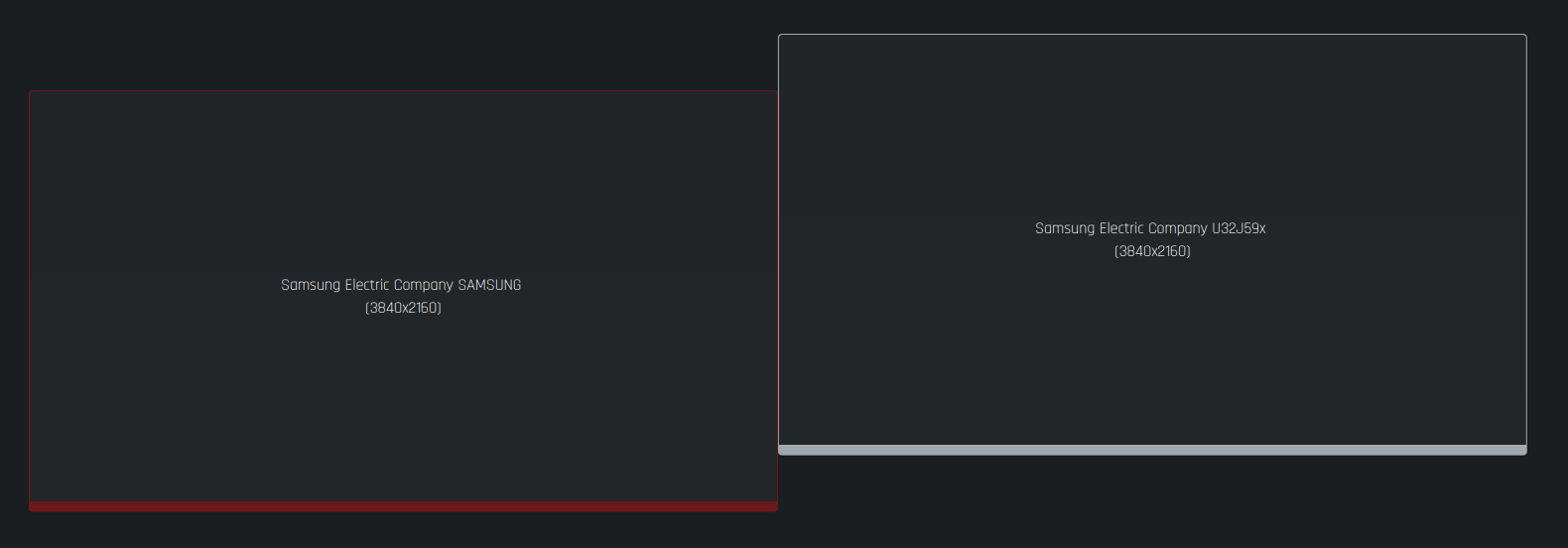

Consider this display layout.

My monitors are both the same width and height, and to make the math easier later on, we’ll assume that they are both 100x100.

My left monitor is aligned a 10th of the way down from the top of my right monitor. In real life, I have a dual-arm monitor stand that can’t be individually height-adjusted, so we must arrange them in software as close as possible. (If you don’t, then text will be incredibly confusing to read when zoomed in and flowing between your screens.)

So the left screen, will be at (0, 10). Therefore the right screen must be at (100, 0) because`of the fact it’s directly to the right of the other screen.

The virtualScreenSize() method described above draws an imaginary tight rectangle around all of these screens. It returns the resulting size of that rectangle.

What zoom does

Zoom checks the visual position of the mouse against this imaginary rectangle. Let’s look at the first two checks:

if (x < threshold) {

xMove = (x - threshold) / zoom;

} else if (x + threshold > screenSize.width()) {

xMove = (x + threshold - screenSize.width()) / zoom;

}

The first one is simple. We check if x is less than threshold (which is 4). We’re checking if the mouse is less than 4 units in from the left side of the rectangle, and panning to the left if it is.

The second check is the exact same, except we are checking if the mouse is less than 4 units from the right side of the rectangle, and panning to the right if it is.

We can guess that the next two checks are the same, but we’re working in the vertical dimension (so, checking y, panning up near the top, and panning down near the bottom).

if (y < threshold) {

yMove = (y - threshold) / zoom;

} else if (y + threshold > screenSize.height()) {

yMove = (y + threshold - screenSize.height()) / zoom;

}

Which is correct.

Let’s try to pan.

Try to imagine this scenario in your head. You’re sitting at a desk with two screens, running KDE. Each screen is 100x100, and is configured in the layout I described above.

Let’s zoom out to 100%, turning the zoom off effectively.

- Move your mouse to the center of the left screen

(50, 50). - Now, zoom in by a factor of 1.1. The mouse will still be near where it started, and will still be on the left screen. Keep it where it is.

- Now, move straight up until your mouse just barely touches the top of your left monitor.

- Notice how the mouse is still visible.

- Try moving up just a little bit more until you notice the mouse going slightly off-screen.

You have just caused the bug. Your cursor is showing it to you. The cursor has gone off-screen on the top edge of a monitor! This will never happen if you’re zoomed out. This will only happen on bottom and right edges because of how the cursor is shaped, but never the top!

So what happened?

Go back to step 4. Try to reason about where the cursor is, according to the zoom effect’s calculation of x and y.

// x = 50

// threshold = 4

// screensize.width() = 200

if (50 < 4) { // never true

xMove = (50 - 4) / zoom;

} else if (50 + 4 > 200 { // never true

xMove = (50 + 4 - 200) / zoom;

}

If you moved the mouse straight up, we know for a fact that x is currently 50. So it won’t affect the first two bounds-checks on x, so we never pan horizontally, and that’s fine. But let’s look at y.

If we recall correctly, the top edge of the left screen will be at 10. If we look at where the mouse cursor is by step 4 above, it will be right there at y=10 according to the zoom effect.

// y = 10

// threshold = 4

// screenHeight = 110

if (10 < 4) { // never true

yMove = (10 - 4) / zoom;

} else if (10 + 4 > 110) { // never true

yMove = (10 + 4 - 110) / zoom;

}

Remember at step 5 when the mouse went off-screen? This is why.

The mouse never reached the threshold, so we never got to pan in any direction.

How I fixed it

The way to fix this is to ensure we pan at the edges of an actual screen. We must pan at the edges of the screen the mouse is currently visible on.

Luckily, KDE already has an API for this. So we can get that screen, and we can call it the current screen or currScreen.

const QRectF currScreen = effects->screenAt(QPoint(x, y))->geometry();

We can now adjust the bounds check to use the bounds of the current screen, like so:

// bounds of the screen the cursor's on

const int screenTop = currScreen.top();

const int screenLeft = currScreen.left();

const int screenRight = currScreen.right();

const int screenBottom = currScreen.bottom();

if (x < screenLeft + threshold) {

xMove = (x - threshold - screenLeft) / zoom;

} else if (x > screenRight - threshold) {

xMove = (x + threshold - screenRight) / zoom;

}

if (y < screenTop + threshold) {

yMove = (y - threshold - screenTop) / zoom;

} else if (y > screenBottom - threshold) {

yMove = (y + threshold - screenBottom) / zoom;

}

But, hey! If we pan on the current screen’s edges, won’t that stop the mouse being able to go to other screens? Yes, yes it will. So we must find whether there’s a screen adjacent to each edge of the current screen. KDE has a mechanism for this, and I wrote a screenExistsAt() method to make it easier to access.

const int screenCenterX = currScreen.center().x();

const int screenCenterY = currScreen.center().y();

// figure out whether we have adjacent displays in all 4 directions

// We pan within the screen in directions where there are no adjacent screens.

const bool adjacentLeft = screenExistsAt(QPoint(screenLeft - 1, screenCenterY));

const bool adjacentRight = screenExistsAt(QPoint(screenRight + 1, screenCenterY));

const bool adjacentTop = screenExistsAt(QPoint(screenCenterX, screenTop - 1));

const bool adjacentBottom = screenExistsAt(QPoint(screenCenterX, screenBottom + 1));

Essentially we’re casting a ray in all 4 cardial directions from the center of the current screen. If we hit another screen, then we’ll get true. We’ll get false otherwise. We can then check if the relevant edge is adjacent to another screen during the bounds check.

if (x < screenLeft + threshold && !adjacentLeft) {

xMove = (x - threshold - screenLeft) / zoom;

} else if (x > screenRight - threshold && !adjacentRight) {

xMove = (x + threshold - screenRight) / zoom;

}

if (y < screenTop + threshold && !adjacentTop) {

yMove = (y - threshold - screenTop) / zoom;

} else if (y > screenBottom - threshold && !adjacentBottom) {

yMove = (y + threshold - screenBottom) / zoom;

}

This allows the mouse to pass through adjacent edges without panning the screen.

Some notes and bugs this causes

This isn’t a perfect solution, but really helps.

First of all, in 6.0, we needed to remove the clamping of the zoom area. This is because it caused weird subtle issues with the new panning behaviour, and it was more reliable to disable it.

if (xMove) {

prevPoint.setX(prevPoint.x() + xMove);

}g

if (yMove) {

prevPoint.setY(prevPoint.y() + yMove);

}

Ultimately this means it’s possible to get the zoom area to go off-screen, but this isn’t a big deal since KWin will just show black instead of garbage memory.Moving the mouse will help you pan the zoom area back into viewing the workspace.

We’re also casting from the center of the current screen. In certain extreme layouts, some screens won’t have another screen along any direction from that point of the screen. So the mouse will get stuck on that screen even though there’s another screen it could jump to.

Going forward

Despite the two issues above, I was able to get the fix merged into KDE Plasma 6. If you’re on Arch Linux and other rolling distros, you already have the fix.

And it’s working really well. I’m using it to write this article.

I plan to address the two bugs in a future merge request, but if you think you have an idea for how to solve them then there’s no time like the present to get involved with contributing to KDE. Even if you’re a beginner and just want to help, like I was, there are plenty of talented people willing to help.

What other compositors can learn from KDE here

I assert and maintain that you should copy the Windows magnifier if you’re going to implement a zoom feature. Writing a screen magnifier is very difficult done right, and you can’t be super opinionated about how to implement it. Like many accessibility tools, there is an objectively correct way to do a magnifier and you should be following it to the letter. Microsoft, in this regard, sets the standard. KDE comes extremely close.

If you’re a compositor dev, here’s how you should implement a zoom feature if you decide to.

Implement a virtual workspace!!!

You must render all physical screens to an off-screen virtual workspace like both KDE and Windows do. You should render black rectangles in areas where tere isn’t a screen, then blit the relevant portions of the virtual screen out to the physical displays. This will genuinely make your life easier, since now your compositor can apply a translation to the virtual workspace and you’ve already implemented the actual zoom part of a magnifier right there.

An alternative could be doing this on the GPU via a vertex shader that applies the zoom camera transformation to all Wayland surfaces. This means you aren’t allocating another (or potentially multiple other) framebuffers in the GPU’s memory.

However you decide to do it, you must if you want a screen magnifier. I’m looking at older compositors, such as Compiz, which do zoom on a per-monitor basis and it’s not a nice experience.

While I don’t have experience with other wlroots-based compositors, I do know that Hyprland also behaves like Compiz in regards to zoom. This is because Hyprland renders each screen individually, and the zoom effect is handled for each screen individually as a result. I’d encourage someone with better experience than me to submit a merge request fixing this, if you want to.

”Proportional” should not be the default or only option for tracking.

You should make a push tracking option and make it the default. If people prefer proprtional, they can change it in settings - but proportional movement is extremely disorienting and makes it hard to read things if the mouse is in the way.

Test with two screens!

Test your compositor’s zoom feature with two screens, and see if it’s natural or fun to use. If you feel annoyed using it, then a blind person will as well and can’t use your compositor to begin with.

Magnifiers are hard.

The reason no Linux desktop gets the screen magnifier right isn’t the fault of the people who wrote it.

As with many other accessibility-related things, there is a science to it. Magnifiers have to deal with so many use cases and can’t just decide to fail. They’re extremely difficult to write.

So, that’s basically it.

Hopefully you guys found that interesting or maybe even learned something. Maybe you learned some code, or maybe you learned something about how I use the computer blind. Either way, I’m glad that I was able to improve the Linux desktop in a small yet profound way for many people just like me.

If you want to learn more about what I do and how I do it, then maybe you’ll enjoy this Tech Over Tea episode.

Or, hell, just explore the site a bit. I recommend this page. Or, maybe you liked what you just read and wouldn’t mind buying me a coffee to help support my work? :heart: (wait crap I never implemented emoji)